O KONFERENCJI

ROLA RELIGII W FILOZOFII POLITYCZNEJ I ETYCE IMMANUELA KANTA, 14-16.05.2025

Dla Kanta filozofia religii jest tematem o fundamentalnym znaczeniu. Zajmuje się nim szczególnie w dziele Religia w obrębie samego rozumu (1793). Pozostając w duchu Oświecenia, Kant stanowczo sprzeciwia się wszelkim formom spekulatywnej wybujałości, przesądom, duchowemu fanatyzmowi i dogmatyzmowi opartemu na objawieniu. Zamiast tego dąży do zredukowania religii do tego, co można obronić przy pomocy rozumu. Zdaniem Kanta, zasady religijne i objawione nakazy są filozoficznie akceptowalne jedynie w takim zakresie, w jakim można je pogodzić z wymogami rozumu i moralności. Na przykład nie ma miejsca na wiarę w cuda (Religia w obrębie samego rozumu, Kraków 1993, s. 111–117). Pojawia się natomiast pytanie: czy filozoficzne wysiłki, aby radykalnie zracjonalizować religie i zredukować je do rozumnego fundamentu moralnego, są same w sobie rozumne?

W ramach konferencji podjęty zostanie szereg problemów naukowych. Przede wszystkim obejmują one:

(1) analizę Kantowskiego rozumienia religii (tj. znaczenia rozróżnienia między „religią jako służbą Bożą” a „czysto moralną religią”, jak również rozróżnienia między „wiarą kościelną” a „czystą wiarą religijną”);

(2) problem związku między filozofią religii a filozofią historii w myśli Kanta (ponieważ powiązanie tych kwestii pozwala na postrzeganie historii ludzkości jako procesu, w którym mamy do czynienia z postępem);

(3) kwestię politycznego znaczenia religii w pismach Kanta, która do tej pory była niedostatecznie analizowana (np. jego pogląd, że „religia jest najwyższą potrzebą państwową” [Spór fakultetów, Dzieła zebrane, t. 5, s. 200]);

(4) Habermasowskie ujęcie relacji między wiarą a rozumem, które jest obecnie szeroko dyskutowane;

(5) pozornie paradoksalne twierdzenia Kanta, który z jednej strony mówi: „Etyka [...] nie potrzebuje ani idei jakiejś innej, wyższej od człowieka, istoty dla poznania swego obowiązku, ani pobudki innej niż samo prawo, dla przestrzegania obowiązku” (Religia w obrębie samego rozumu, Kraków 1993, s. 23), a z drugiej strony stwierdza: „etyka [...]prowadzi nieodzownie do religii” (Religia w obrębie samego rozumu, s. 26);

(6) niezwykle trudne pytania dotyczące filozoficznej wartości analiz judaizmu dokonanych przez Kanta w Religii w obrębie samego rozumu oraz interpretację jego poglądów, które wymagają rzetelnych wyjaśnień.

Jak dziś odnosimy się do stanowiska Kanta – zwłaszcza w kontekście dyskusji o religii w przestrzeni publicznej? Współczesne społeczeństwa zachodnie charakteryzują się pluralizmem religii, które są ze sobą niekompatybilne. Dla dobra pokoju społecznego religie te zostały sprywatyzowane, a w państwach liberalnych obowiązuje zasada neutralności. Jednak do jakiego stopnia państwo powinno zachowywać tę neutralność? Czy powinno jedynie unikać stronniczości, czy też musi być aktywnie laickie (jak we Francji)? Jakie rozwiązania proponuje Kant i które z nich możemy uznać za możliwe do zaakceptowania w dzisiejszych warunkach?

Odpowiedź na te pytania jest istotna zarówno z punktu widzenia ogólnej refleksji nad spójnością i aktualnością oświeceniowego podejścia Kanta do religii, jak i w kontekście naszych współczesnych poglądów na religię oraz jej miejsca w sferze publicznej.

REJESTRACJA

Rejestracja wymagana jest zarówno w przypadku uczestników aktywnych (z referatem) oraz uczestników biernych. Rejestracji należy dokonać przy pomocy formularza rejestracyjnego.

ZAPROSZENI WYKŁADOWCY

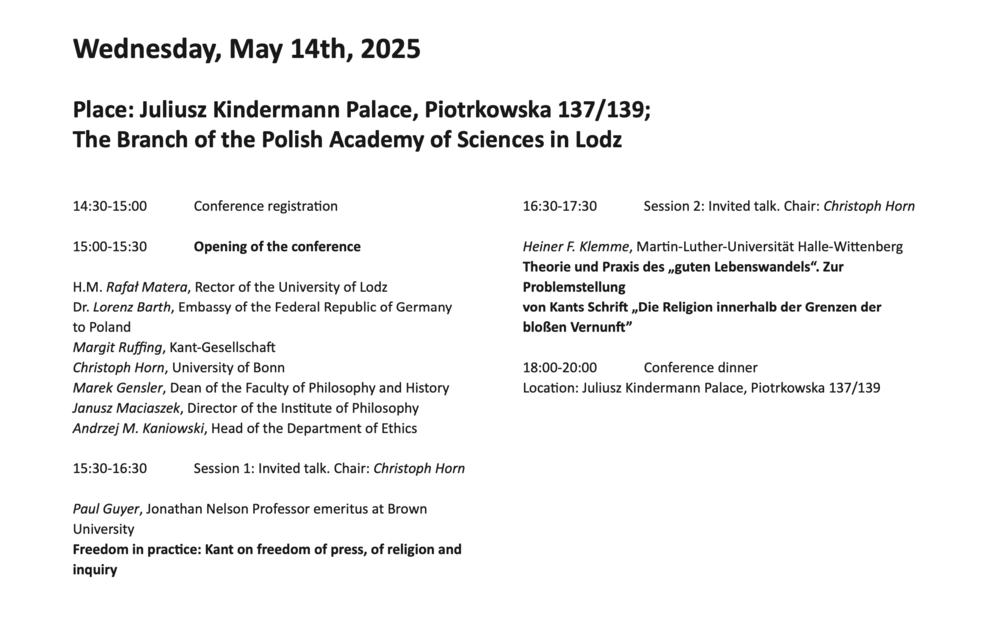

- Paul Guyer - Jonathan Nelson Professor emeritus of Humanities and Philosophy, Brown University.

- Christoph Horn - Professor and Director of Practical Philosophy and Ancient Philosophy at the University of Bonn.

- Heiner F. Klemme - Professor of Philosophy at Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg.

REGULAMIN KONFERENCJI

Regulamin konferencji jest dostępny tutaj: https://tinyurl.com/rmr4cku4 (wersja polska), https://tinyurl.com/5bxxfwuk (wersja angielska).

OPŁATY

W konferencji możliwe jest uczestnictwo czynne (z referatem) oraz bierne (bez referatu).

Czynny udział w konferencji (z referatem) jest płatny. Opłata konferencyjna wynosi:

- 400 zł (90 euro)

- 200 zł (45 euro) dla studentów i doktorantów

Opłatę należy wnieść do 07.05.2025 r. przelewem na konto bankowe Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego:

Bank Polska Kasa Opieki Spółka Akcyjna

83 1240 3028 1111 0011 4849 4748

for foreign transfers:

IBAN: PL83 1240 3028 1111 0011 4849 4748

BIC/SWIFT: PKOPPLPW

z dopiskiem: konferencja THE ROLE OF RELIGION

Bierny udział w konferencji jest bezpłatny.

ABSTRAKTY

- Paul Guyer

Freedom in practice: Kant on freedom of press, religion, and inquiry

Freedom of pen and press, of religion, and the underlying freedom of inquiry are the forms of freedom with which Kant was most concerned in the political context (and with which we continue to need to be deeply concerned). For Kant these forms of freedom follow directly from the innate right to freedom, and need no further justification, as for example in J.S. mill's utilitarian approach. I analyze the rights and duties of both governed and governors that arise from these duties. - Heiner F. Klemme –Theorie und Praxis des „guten Lebenswandels“. Zur Problemstellung von Kants Schrift „Die Religion innerhalb der Grenzen der bloßen Vernunft“

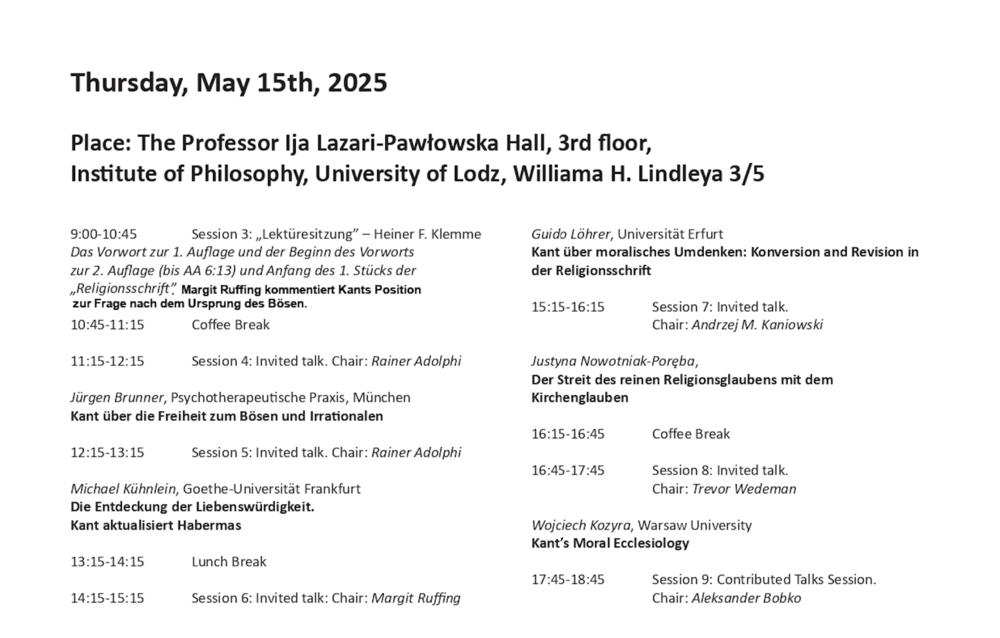

Based on reflections on the interpretation of the title of Kant's Religion, I argue that Kant’s intention in that work was both negative-critical and positive-critical. The negative-critical intention states that we can lead a life pleasing to God only through moral action. The positive-critical intention states that, within certain limits, religion can make a significant contribution to our moral actions, although articles of faith and religious practices cannot be derived from pure reason. It becomes apparent that, in the Religion, Kant not only seeks to overcome the difference between the theory and practice of our moral actions “in theory,” but also strives to exert a direct influence on the moral actions of his contemporaries and on state action. The linchpin concept of this work proves to be that of “good life conduct” (“guter Lebenswandel”). - Jürgen Brunner

Kant über die Freiheit zum Bösen und Irrationalen

In meinem Beitrag geht es um die handlungstheoretischen Grundlagen von Immanuel Kants Konzeption einer Freiheit zum Bösen und Irrationalen. Als Interpretationshilfe habe ich Alexander Gottlieb Baumgartens Vermögenspsychologie verwendet. Ich argumentiere für drei Thesen:

(1) Baumgarten und Kant vertreten das libertarische Anderskönnen unter gegebenen Umständen. Das Anderskönnen ist allerdings nicht das Definiens von moralischer Freiheit. Das Definitionskriterium ist die Fähigkeit zur Autonomie. Baumgartens und Kants Freiheitskonzeption interpretiere ich als akteurskausal und fähigkeitsbasiert.

(2) Kants Begriff der transzendentalen Freiheit kann als Weiterentwicklung der fähigkeitsbasierten (vermögenspsychologischen) Freiheitskonzeption Baumgartens verstanden werden. Baumgarten definiert freie Selbstdetermination (determinatio libera) als freiwillige Selbstverpflichtung (necessitatio). Nach Kant sind wir transzendental frei, weil wir zur Autonomie fähig sind. Irrationale und böse Handlungen lassen sich als zurechenbarer Verzicht auf Autonomie und als vorwerfbare Entscheidung für Heteronomie auffassen.

(3) Kant vertritt im Anschluss an Baumgarten einen graduellen Freiheitsbegriff. Der Grad der aktualisierten Freiheit hängt von der moralischen Motivation ab. In absteigender Reihenfolge lassen sich drei Grade differenzieren: Moralität (Handlungen rein aus Pflicht), Legalität (Unlauterkeit) und vorsätzliche Pflichtverletzungen (Bösartigkeit). Kant knüpft unmittelbar an Baumgartens graduellen Freiheitsbegriff an. Eine Handlung erfolgt Baumgarten zufolge nur dann nach reiner Freiheit (libertas pura), wenn keine anderen Handlungsmotive außer der objektiven Verpflichtung (moralitas obiectiva) eine Rolle spielen. Der Grad der Freiheitseinschränkung ist nach Baumgarten abhängig von dem Anteil an beigemischter sinnlicher Willkür (arbitrium sensitivum) und von der introspektiven Intransparenz der Triebfedern (elateres animi). - Michael Kühnlein

Die Entdeckung der Liebenswürdigkeit.Kant aktualisiert Habermas[The discovery of kindness. Kant updates Habermas]

[GER] Bekanntlich lehnt Habermas die Kantische Postulatenlehre als funktionalistisch ab. Deshalb muss sie aus seiner Sicht auch nicht erst in säkulare Lernprozesse der Vernunft übersetzt werden, allenfalls kann sie dadurch ersetzt werden. In seinen Spätschriften setzt Kant jedoch eine andere Pointe. Am Beispiel der Liebenswürdigkeit, den Kant gegen einen dogmatischen Säkularismus ins Felde führt, verteidigt er den liberalen Mehrwert einer christlichen Denkungsart unter nachmetaphysischen Bedingungen der Moderne.

[ENG] As is well known, Habermas rejects Kant's doctrine of postulates as functionalist. Therefore, in his view, it does not need to be translated into secular learning processes of reason; at best, it can be replaced by them. In his late writings, however, Kant sets a different point. Using the example of kindness, which Kant uses against dogmatic secularism, he defends the liberal added value of a Christian way of thinking under the post-metaphysical conditions of modernity. - Guido Löhrer

Kant über moralisches Umdenken: Konversion and Revision in der Religionsschrift [Kant on Moral Rethinking: Conversion and Reversion in Religion]

[GER] Moral und die Idee eines höchsten Gutes führen unumgänglich zur Religion, behauptet Kant im ersten Stück der Religionsschrift. Denn für dieses Gut bedarf es eines Gottes, der Glückseligkeit nach dem Maß menschlicher Glückswürdigkeit ausschüttet, und für die Glückswürdigkeit einer Maxime, die die Willkür sich für den Gebrauch ihrer Freiheit auferlegt. Mit Letzterem stellt sich nicht nur die Frage, wie eine Triebfeder Gegenstand einer Maxime sein kann. Kant handelt sich damit auch ein veritables Problem mit dem Ursprung des subjektiven Grunds dieses Freiheitsgebrauchs ein. Dessen Lösung entwirft er sowohl als Revision in einem unendlichen Progress als auch als jähe Konversion oder Revolution der Gesinnung. Beide Formen moralischen Umdenkens sollen sich als miteinander vereinbar erweisen, wenn man wiederum Religion voraussetzt oder zumindest einen göttlichen Eternalismus. Doch dürfte der Ansatz mehr Probleme aufwerfen, als er löst.

[ENG] Morality and the idea of a supreme good inevitably lead to religion, Kant claims in the first part of his Religionsschrift. For this good requires a God who distributes happiness according to the human being’s worthiness to be happy, and for the worthiness to be happy a moral maxim which the power of choice imposes on itself for the exercise of its freedom. The latter not only raises the question of how an incentive can be the subject of a maxim. Kant thus also faces a serious problem regarding the origin of the subjective ground for that exercise of freedom. He outlines his solution both as a revision in an infinite progress and as a radical conversion or revolution in disposition. Both types of moral rethinking are thought to prove compatible with each other if one presupposes religion or at least a divine eternalism. However, this approach is likely to raise more problems than it solves. - Justyna Nowotniak-Poręba

Der Streit des reinen Religionsglaubens mit dem Kirchenglauben

Den reinen Vernunftglauben setzt Kant als die gemeinsame Ebene im Streit der zwei Glaubensweisen, die den Frieden zwischen beiden möglich macht. Der Geschichtsglaube soll stufenweise alles Äußere des Gottesdienstes abwerfen und die Menschen würden nur die unsichtbare Kirche, i.e. ein ethisches gemeines Wesen bauen. Dieser philosophischen Vorstellung steht aber der wirkliche Streit beider Glaubensweisen entgegen. Der Kirchenglaube wehrt sich mit seinen Statuten gegen die rein vernünftige Begründung der Moral, die in einer guten Lebensweise besteht und keine Gnadenwirkungen voraussetzt. Im Gegensatz dazu sucht der Kirchengläubige, durch Afterdienst Gott gefälling zu werden. Es fragt sich, ob der auf Gewissenszwang und Ritualen beruhende Religionsglaube nicht auf der Seite des Bösen im Sinne der verkehrten Ordnung der Maximen des Handelns steht. - Wojciech Kozyra

Kant’s Moral Ecclesiology

Contrary to what the actual status questionis might suggest (studies devoted to the subject are scarce), Kant has an elaborate ecclesiology, or theory of the Church. He operates with traditional Christian ecclesiological categories; especially when he distinguishes between the visible Church (ecclesia visibilis), the invisible Church (ecclesia invisibilis), the Church militant (ecclesia militans), and the Church triumphant (ecclesia triumphans). Despite his criticism of religion based on history and ritual, Kant emphasizes the importance of the visible Church as an agent of enlightenment and defines – in moral terms – the marks of its veracity, which is meant to enable the identification of the true visible Church in history. Kant develops his ecclesiology with an awareness of, and in contrast to, the Pietist tradition, as well as the Lockean understanding of the Church which in Germany found support from thinkers such as Moses Mendelssohn and Gottfried Achenwall. My contribution will present Kant’s notion of the Church in its proper context, and in particular will focus on a seemingly paradoxical consequence of Kant’s moralized ecclesiology: its exclusivity. - Beatrice Sasha Kobow

The Inner Freedom of the Categorical Imperative and the Need for a Moral Community

In 'Träume eines Geistersehers', Kant rejects the idea that we can know anything about an afterlife, but remarks ironically that any judgment about our performance will depend on how well we have managed our position in this life. For Kant, this performance is a careful balancing act between our public post and the private development of our freedom. In 'Geisterseher', he refers us to Candide's garden, in 'Was ist Aufklärung?' he points us towards the shared space of a self-enlightening public (with its organs, such as newspapers). I would like to investigate Herta Nagl-Docekal's interpretation of 'inner freedom' as she criticises Habermas and Rawls and focuses on Kant's notion of a community which is 'church-like' and on which we depend for our moral standing as individuals. This, I believe, will allow a speculation as to who might be considered 'the judges' of our performance - it is contemporary and future participants of this community of moral agents. It is they we have in mind when formulating the categorical imperative as a guardrail of our individual exercise of freedom (in its various existing and further formulations and application to our actions). - Trevor Wedman

Faith - Revelation - Reason

The distinction between faith and reason presents a dichotomy reaching back to Kant’s exclusion of religion from theoretical reason, and perhaps even to Luther’s insistence on sola fide and sola scriptura. More recently, the encyclical Fides et Ratio sought to reconcile faith with reason in arguing that faith without reason leads to superstition while reason without faith leads to relativism or even nihilism. However, Habermas, responding in part to Benedict XVI’s Regensburg Lecture, has called into question the need for such a reconciliation of faith with reason in an age which has seen the arrival of secular reason. The modern scientific, ‘post-metaphysical’ worldview, Habermas seems to indicate, constitutes its own discourse while needing neither faith nor reason as traditionally conceived. The proposed contribution will use the occasion of Habermas’ critique to evaluate and question the faith-reason dichotomy within Kant’s critical writings. It will seek to resolve the dichotomy by resorting to Hermann Cohen’s notion of revelation and “second-law” as found in his “Religion der Vernunft aus den Quellen des Judentums”. Here ‘revelation’, law, or even normativity proves itself as the transcendental coin of which faith and reason are merely the sides. - Aleksander Bobko

Kant's political thinking

In this article I attempt to show a connection between Kant’s transcendental philosophy and his political thinking. It means, that political thinking can build a specific relationship between the sphere of nature (theoretical reason) and freedom (practical reason). As a result the highest political good (eternal peace), which should be achieved by humanity, can be interpreted as the most complete form of rationality, whose source is reason. The realization of such a goal can only be thought of hypothetically. - Christoph Horn

How to understand Kant’s philosophy of history?

Kant’s philosophy of history has always presented considerable difficulties of interpretation for its readers. When we look at the relevant texts we certainly receive the impression that Kant seriously wants to defend a relatively unambiguous position in relation to the philosophy of history; and at the very least he seems throughout to endorse the basic thought that the course of history exhibits a specific logic that is bound up with the development of human capacities and with the idea of political progress; and he always holds that some kind of cosmopolitan social and political order stands at the end of history. On the other hand, this position does not seem to sit particularly well with Kant’s other philosophical convictions either in the context of his theoretical or of his practical philosophy. For Kant makes concessions to certain positions (usually regarded as quite un-Kantian) which involve a ‘metaphysical dogmatism’, such as a Stoic conception of natural teleology, an Aristotelian essentialism, a perfectionism in relation to the human species, and a providential theology. He also repeatedly speaks of ‘nature’ as if human history unfolded under its guidance or even in an ‘automatic’ or ‘mechanical’ manner. These are all claims which seem to threaten Kant’s central idea of moral autonomy. - Bartosz Wesół

Religion, Ethics and Practical Reality

In my talk, I will argue that the alleged paradox between the statements that “morality” does not need “the idea of another being above” the human being (AA VI, 3); and that it “inevitably leads to religion” (AA VI, 6) can be better understood from the perspective of, often ambiguous, Kantian conceptions of reality (Realität), practical reality (praktische Realität), and existence (Existenz) in reference to God.

The main shift between the First and the Second Critique is marked by the fact that in the former Kant denies the possibility of proving the existence of God, but in the latter grounds the practical reality of the postulates of practical reason. This creates tension, which is also apparent in his further philosophical writings.

In my view, the notion of practical reality is the key to understanding the relationship between ethics and religion in Kant. Even in the Critique of Pure Reason, he struggles with the notion of existence in saying that as a category of modality it is only “subjectively synthetic” (A234) and can be “objectified” by the universal appeal to other subjects. In the theoretical domain, the synthetic connection between a real object and a (subjective) concept is established through sensual intuition.

In the practical domain, the objectivity of the postulates is ensured by the universality of the moral law, the synthetic connection is established by the actions of the will. The former corresponds to ethics which is only concerned with the universal rules of conduct, the latter however entails embodying the moral law in practice which is the gist of Kant’s understanding of religion. - Seniye Tilev

Faith and Teleology: Kant on the Rational Completeness of Morality

In this paper, I argue that, according to Kant, the rational completeness of morality is achieved through moral faith, as it provides a context for moral experience. A common misconception about religiously oriented readings of the highest good is to see it merely as a divine reward for the virtuous in eternity. Both secular readers and those admitting the regulative force of faith often ignore its significance for present affairs, overemphasizing motivation or psychological consolation based on a future promise of happiness. I argue that critical religiosity, focused on realizing the highest good in this world, seeks harmony between nature and morals through reflective judgment. This immanent hope for a teleological conception of moral experience complements the ideal moral world, even if we remain agnostic about its full realization.

In the third Critique, teleology—including the intentionality of the divine author of morals and nature—plays a substantial role beyond guaranteeing future happiness. Moral attachment to the claim of the highest good operates within present moral experience, regardless of its fulfillment in a future world. Teleologically considered, the highest good becomes not only the final end but “a supreme cause of the world” (KU 5:444). Although it proves nothing for the nonbeliever, it establishes unity between nature and morals. In this moral view, God is not a future judge but an idea uniting all states of affairs here, now, and beyond. Neither the duty to promote the highest good nor the moral law loses bindingness without rational faith, but rational completeness suffers as reason loses alliances in nature and history. Reason would remain imprisoned in pure rationality, shattering the efficacy of moral agency.

Thus, Kant contends that “the final purpose that morality imposes upon us cannot exist without theology, for then reason would be at a loss with regard to that final end” (KU 5:484). If the agent views life as being thrown into blind nature and death as a return to chaos (KU 5:452), her moral domain collapses. More than losing motivation or consolation, the agent loses relation to her own purposiveness voiced in the moral law. Kant’s moral teleology concerns reason’s inherent purposiveness, demanding actualization. The idea of God does not serve as a mere gap-filler or psychological comfort but constitutes a substantial part of moral experience. Thus, for the virtuous atheist, morality cannot realize any systematic, comprehensive harmony.

ORGANIZATORZY I SPONSORZY

- Projekt dofinansowany ze środków Polskiej Akademii Nauk i Polsko-Niemieckiej Fundacji na rzecz Nauki (Deutsch-Polnische Wissenschaftsstiftung)

- Towarzystwo Immanuela Kanta (Kant-Gesellschaft e.V.)

- Polska Akademia Nauk Oddział w Łodzi/Komisja Etyki

- Uniwersytet Łódzki, Katedra Etyki, Instytut Filozofii

- Uniwersytet w Bonn, Instytut Filozofii

- Patronat Honorowy Rektora Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego

- Polskie Towarzystwo Filozoficzne, Oddział w Łodzi

POPRZEDNIE EDYCJE

- 2024: Kant and his significance for the present – Kant und seine Bedeutung für die Gegenwart

- 2022: Visions of good life in the Antiquity – physical, spiritual and social. Ancient Medicine and Philosophy

- 2021: Christianity and Democracy / Christentum und Demokratie

- 2019: Celebrating the philosophical and intellectual achievements of Jürgen Habermas / Philosoph und Intellektueller in Zeiten des Umbruchs. Zur Würdigung des Werks von Jürgen Habermas aus Anlass seines 90. Geburtstages

- 2018: Europe as an Idea and as a Viable Project founded on «Logos» / Europa als eine Idee und als ein tragfähiges Projekt gegründet auf «Logos»

- 2017: Früherer und Zeitgenössischer Sinn und Begriff von Weisheit

- 2016: The Idea and the Practice of Republicanism

- 2015: Moral Universalism and Non-ideal Normativity / Nichtideale Normativität

- 2014: Human Rights: from Theoretical Justifications to Dilemmas of Practical Applications

MEDIA

W roku 2010, nim zainicjowano organizowanie cyklicznej konferencji pod wspólną nazwą «Normativity & Praxis», Katedra Etyki zorganizowała – w ramach projektu Aktualność i praktyczne znaczenie filozofii państwa i prawa Immanuela Kanta (numer projektu: N101249434 [2494/B/H03/2008/34]) – międzynarodową konferencję „The Topicality of Kant's Philosophy of State and Law”, tematycznie pokrewną konferencji organizowanej w roku 2025 The Role of Religion in Kant's Political Philosophy and Ethics. Przy okazji konferencji organizowanej w roku 2010 mgr Ewa Wyrębska, wówczas doktorantka i asystentka zatrudniona w Katedrze Etyki Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego, przeprowadziła wywiady z następującymi referentami ówczesnej konferencji: prof. Paulem Guyerem, prof. Reinharden Brandtem, prof. Berndem Ludwigiem i prof. Alessandro Pinzanim.